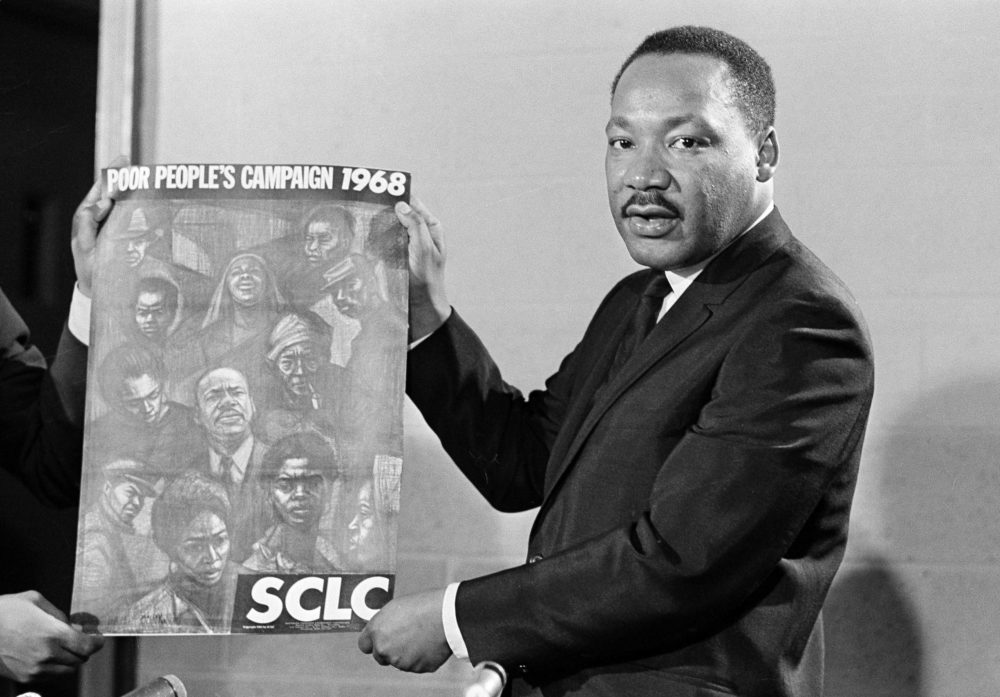

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor on MLK’s Radical Anticapitalism

In this short excerpt from the book Fifty Years Since MLK, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor examines MLK’s turn towards a radical critique of capitalism before his life was cut short.

In a posthumously published essay, Martin Luther King, Jr. pointed out that the “black revolution” had gone beyond the “rights of Negroes.” The struggle, he said, is “forcing America to face all of its interrelated flaws—racism, poverty, militarism and materialism. It is exposing the evils that are rooted deeply in the whole structure of our society. It reveals systemic rather than superficial flaws and suggests that radical reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced.”

But it had not started out that way. Over the course of a decade, the black struggle opened up a deeper interrogation of U.S. society, and King’s politics traversed the same course.

Indeed, in the early 1960s, the Southern movement coalesced around the clearly defined demands to end Jim Crow segregation and secure the right of African Americans to unfettered access to the franchise. With clear targets and barometers for progress or failure, a broad social movement was able to uproot these systems of oppression. King was lauded as a tactician as well as someone who could articulate the grievances and aspirations of black Southerners.

But despite the successful example of nonviolent civil disobedience across the South, it appeared to have little, if any, lasting impact on the edifice of racial discrimination that defined black life elsewhere. Indeed, the seeming permanence of black marginalization across the United States produced hundreds of urban uprisings in the middle of the 1960s. If King’s strategic genius in the South was deploying nonviolent civil disobedience to disarm Southern racists while coercing the political establishment into securing first-class citizen rights, it was a strategy that ultimately failed in cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. In those places, obnoxious signs of Jim Crow were not the problem; rather, it was the insidious but obscured actions of the real-estate broker, the banker, the employer, the police officer, and other agents that maintained racial inequality.

As King’s attention drifted from the South to the entrenched northern ghettos, he faced denunciations and chastisement from former allies in the North. These people had supported him so long as he confined his demands to ending legal discrimination. Indeed, because Southern racism was rendered as antiquated and regressive, King was celebrated for helping to pull the South toward progress and modernity. But even as the civil rights movement was valorized for its intervention in the South, it was demonized when it brought its call for black power and liberation to the North—a dynamic that continues to the present day.

Excerpted from Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s contribution to the book Fifty Years Since MLK, edited by Brandon Terry. Continue reading at The Paris Review.